Why Smith Machine Squats Are Harder: The Science Behind the Struggle

Why Smith Machine Squats Are Harder: The Science Behind the Struggle

Smith machines force your body into a fixed vertical bar path that restricts natural movement patterns. Studies show free weight squats produce 43% higher total muscle activation compared to Smith machine squats. This article breaks down the biomechanical and physiological reasons why smith machine squats are harder than they appear.

The Fixed Bar Path Problem: Why Your Body Can't Move Naturally

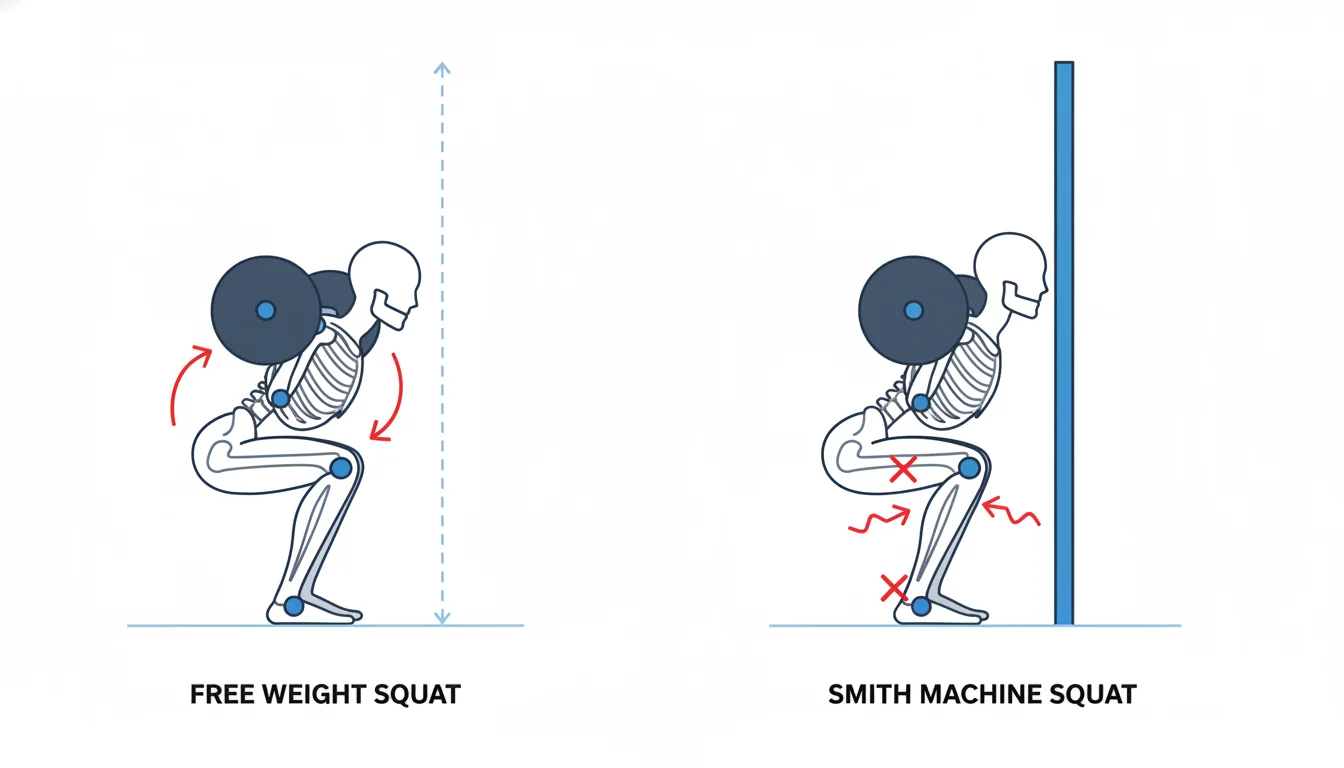

The vertical track eliminates the slight diagonal bar path your body naturally follows during a free weight squat. This restriction forces compensatory joint angles that increase stress on your knees and lower back.

During a barbell squat, the bar travels in a subtle S-curve pattern. Your torso leans forward as you descend, your hips shift back, and the bar path adjusts to keep weight centered over your midfoot. The Smith machine eliminates all of this.

| Factor | Free Weight Squat | Smith Machine Squat |

|---|

| Bar path | Natural diagonal curve | Strictly vertical |

|---|---|---|

| Knee position | Variable based on depth | Often forced beyond toes |

| Hip hinge | Full natural movement | Restricted by fixed track |

| Torso angle | Adjusts automatically | Limited adjustment ability |

| Shear force on knees | Distributed across joints | Concentrated on knee joint |

Your femur length and torso proportions determine your ideal squat mechanics. Someone with long femurs needs more forward lean to stay balanced. The Smith machine doesn't care about your anatomy—it demands the same vertical path from everyone.

This creates a mismatch. Lifters with longer legs often report knee pain on Smith machines while feeling fine with barbells. The fixed path forces them into positions their joints weren't designed to handle. NCSF notes these angular forces concentrate stress on the knee joint specifically.

Stabilizer Muscles: The Hidden Challenge of Machine Squats

Removing the balance requirement doesn't make squatting easier. It disrupts the coordinated muscle firing patterns your nervous system developed through years of movement.

Free weight squats activate stabilizers throughout your entire kinetic chain. Your core muscles brace against rotation, ankle stabilizers fire to prevent lateral drift, and hip muscles engage to control pelvic position. This coordinated effort creates efficient force transfer from the ground through the bar.

Key stabilizers engaged during free weight squats:

- Core complex: Rectus abdominis, obliques, and lumbar erectors stabilize your trunk

- Ankle stabilizers: Gastrocnemius and tibialis anterior control lateral movement

- Hip stabilizers: Gluteus medius and deep hip rotators maintain pelvic alignment

- Knee stabilizers: Vastus medialis and hamstrings co-contract for joint protection

Research shows the gastrocnemius activates 35% more during free weight squats. The biceps femoris shows 26% higher activation. The vastus medialis fires 49% harder. Your body recruits these muscles automatically when it needs to maintain balance.

The Smith machine removes this requirement, giving your stabilizers the day off. But here's the paradox: without stabilizer co-contraction, force transfer becomes less efficient. You're pushing through a movement pattern your neuromuscular system doesn't recognize. [Altas Strength] explains this altered activation pattern contributes to the awkward feeling many lifters report.

Friction and Mechanical Resistance: The Weight Feels Different

Guide rod friction adds 10-20 pounds of resistance that doesn't appear on the weight plates. This hidden load varies throughout the movement and changes based on how well the machine was maintained.

Steel guide rails create friction as the bar travels up and down. Cheap machines or poorly maintained equipment create more friction, while premium machines minimize it. But even the best Smith machine adds resistance you won't find listed anywhere.

| Weight Factor | Impact on Perceived Load |

|---|

| Starting bar weight | 15-25 lbs (vs 45 lb Olympic bar) |

|---|---|

| Guide rod friction | Adds 10-20 lbs variable resistance |

| Counterbalance systems | Reduces effective bar weight |

| Net effect | 135 lbs on Smith ≈ 115-125 lbs free weight |

The counterbalance system complicates things further. Most Smith machines use weights or pneumatic assistance to offset the bar's weight, making the empty bar feel lighter. But the friction adds resistance throughout the movement.

Your brain expects consistent resistance based on the plates loaded. The friction delivers something different: more resistance at the start, less in the middle, and more again near lockout. This inconsistency makes the lift feel harder than the numbers suggest. MajorFitness details how these mechanical factors alter the resistance profile significantly.

Core Activation and Balance: What Changes When the Bar Is Fixed

Your core muscles activate differently when they don't need to prevent the bar from drifting forward or backward. This changes the entire feeling of the squat movement.

Free weight squats demand constant core engagement. Every rep requires your trunk stabilizers to fire milliseconds before your legs push. This anticipatory bracing creates intra-abdominal pressure that protects your spine and transfers force efficiently.

The Smith machine removes the stimulus for this bracing pattern. Your core still works, but it works differently—less anticipatory activation, more reactive compensation. The timing changes and the efficiency drops.

Experienced lifters struggle most with this transition:

- Years of ingrained movement patterns don't transfer

- Proprioceptive feedback feels wrong throughout the lift

- Natural balance adjustments get blocked by the fixed track

- The body searches for stability cues that aren't there

Someone who squats 400 pounds with a barbell might feel awkward with 225 on the Smith machine. Their nervous system expects certain feedback, but the machine provides something alien. This mismatch creates a subjective sense of difficulty that exceeds what the weight alone would suggest.

The first time you switch from years of barbell squats to a Smith machine, the weight feels foreign in a way that's hard to describe. Your body knows something is off.

Body Positioning: Finding the Right Foot Placement

Placing your feet 12-18 inches forward of the bar puts your shins vertical at the bottom position. This counterintuitive stance compensates for the fixed bar path.

Standard squat form doesn't work on the Smith machine. Standing directly under the bar forces your knees too far forward, your heels lift, your lower back rounds, and the movement falls apart.

Optimal positioning adjustments:

- Foot distance: 12-18 inches forward of bar position

- Stance width: Shoulder width or slightly wider

- Toe angle: 15-30 degrees outward

- Shin angle: Vertical or near-vertical at bottom

- Torso position: More upright than free weight squat

Finding your exact position takes experimentation. Start with feet one step forward and perform a bodyweight squat. Note where your knees track, then adjust forward or back until your shins stay relatively vertical throughout the movement.

Common positioning errors include standing too close, using too narrow a stance, and keeping toes pointed straight ahead. Each mistake compounds the joint stress the fixed bar path already creates. [REP Fitness] provides detailed guidance on these positioning variables.

This forward foot position feels completely unnatural at first. You'll want to step back under the bar—resist that urge. The awkward stance protects your knees.

When Smith Machine Squats Are Actually Beneficial

The fixed path that creates problems for some lifters provides advantages for others in specific situations.

Rehabilitation scenarios benefit from reduced balance demands. Someone returning from an ankle sprain can train leg strength without stressing healing ligaments. The machine handles stabilization while tissues recover.

| Use Case | Why Smith Machine Works |

|---|

| Post-injury rehab | Removes balance stress from healing joints |

|---|---|

| Quad isolation | Forward foot position emphasizes quadriceps |

| Solo training | Safety catches eliminate spotter requirement |

| Beginner progression | Simplified movement pattern builds confidence |

| Targeted hypertrophy | Fixed path allows focus on mind-muscle connection |

Bodybuilders use the Smith machine to isolate specific muscles. The forward foot position hammers quadriceps, while a closer stance emphasizes the outer sweep. Strategic positioning creates targeted stimulus that free weights spread across more muscles.

Training alone presents real safety concerns. The Smith machine's rotating safety catches provide a bailout option—fail a rep and you rotate the bar onto the catches. No spotter needed, no risk of getting pinned.

How to Make Smith Machine Squats Work for You

Optimizing your Smith machine squat requires acknowledging its limitations and working within them rather than fighting against them.

Start lighter than you think necessary. The altered mechanics mean your normal squat weight won't translate directly. Use the first few sessions to find positions that feel sustainable, then add weight only after form solidifies.

Programming recommendations by experience level:

- Beginners: Use Smith machine to learn basic squat pattern, then transition to free weights within 4-6 weeks

- Intermediate: Program as accessory movement after main free weight squats

- Advanced: Use for targeted hypertrophy work or deload phases

- Rehabilitation: Follow physical therapist guidance on load progression

Complement Smith machine work with exercises that address its weaknesses. Goblet squats build the balance the machine removes. Planks and Pallof presses maintain core stability. Single-leg work develops the proprioception the fixed path neglects.

Transitioning from Smith machine to free weights requires patience. Drop the weight 20-30% and focus on balance first, depth second, and load third. Your stabilizers need time to catch up to your prime movers. Rushing this transition invites injury.

FAQ

Does the Smith machine bar weigh less than a standard barbell?

Yes. Most Smith machine bars weigh 15-25 pounds due to counterbalance systems, while a standard Olympic barbell weighs 45 pounds. This difference affects how you calculate total weight lifted.

Why do my knees hurt during Smith machine squats?

The fixed vertical bar path forces your knees forward beyond their natural position. Moving your feet 12-18 inches forward of the bar allows more vertical shins and reduces knee stress.

Can I build muscle effectively with Smith machine squats?

Muscle growth occurs through mechanical tension regardless of equipment. Smith machines build quadriceps effectively. Combine with free weight movements to develop stabilizers and functional strength patterns.

Should beginners start with Smith machine or barbell squats?

Beginners benefit from learning proper squat mechanics without balance challenges. Start with Smith machine for 4-6 weeks to build confidence, then transition to barbell squats for complete development.

How much weight should I subtract when switching from Smith to barbell?

Expect to lift 20-30% less weight on your first barbell squat session. Your stabilizer muscles need time to develop, so prioritize form over load during the transition period.

Why do experienced lifters struggle more on the Smith machine?

Years of barbell training develop specific motor patterns and proprioceptive expectations. The Smith machine disrupts these ingrained patterns, creating a sensation of awkwardness despite adequate strength.

Is the Smith machine safer than free weights?

Safety catches allow solo training without a spotter, and the fixed path prevents bar drift. For these reasons, injury risk from losing balance is lower. However, joint stress from the altered mechanics remains a concern.